朋友圈为什么发不出去

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

| Ancient Greek | |

|---|---|

| ?λληνικ? Hellēnik? | |

An inscription about the construction of the statue of Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon, 440/439 BC | |

| Region | Eastern Mediterranean |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Greek alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | grc |

| ISO 639-3 | grc (includes all pre-modern stages) |

| Glottolog | anci1242 |

Map of Ancient (Homeric) Greece | |

Ancient Greek (?λλην?κ?, Hellēnik?; [hell??nik???])[1] includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (c.?1400–1200 BC), Dark Ages (c.?1200–800 BC), the Archaic or Homeric period (c.?800–500 BC), and the Classical period (c.?500–300 BC).[2]

Ancient Greek was the language of Homer and of fifth-century Athenian historians, playwrights, and philosophers. It has contributed many words to English vocabulary and has been a standard subject of study in educational institutions of the Western world since the Renaissance. This article primarily contains information about the Epic and Classical periods of the language, which are the best-attested periods and considered most typical of Ancient Greek.

From the Hellenistic period (c.?300 BC), Ancient Greek was followed by Koine Greek, which is regarded as a separate historical stage, though its earliest form closely resembles Attic Greek, and its latest form approaches Medieval Greek, and Koine may be classified as Ancient Greek in a wider sense – being an ancient rather than medieval form of Greek, though over the centuries increasingly resembling Medieval and Modern Greek.

Ancient Greek comprised several regional dialects, such as Attic, Ionic, Doric, Aeolic, and Arcadocypriot; among them, Attic Greek became the basis of Koine Greek. Just like Koine is often included in Ancient Greek, conversely, Mycenaean Greek is usually treated separately and not always included in Ancient Greek – reflecting the fact that Greek in the first millennium BC is considered prototypical of Ancient Greek.

Dialects

Ancient Greek was a pluricentric language, divided into many dialects. The main dialect groups are Attic and Ionic, Aeolic, Arcadocypriot, and Doric, many of them with several subdivisions. Some dialects are found in standardized literary forms in literature, while others are attested only in inscriptions.

There are also several historical forms. Homeric Greek is a literary form of Archaic Greek (derived primarily from Ionic and Aeolic) used in the epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, and in later poems by other authors.[3] Homeric Greek had significant differences in grammar and pronunciation from Classical Attic and other Classical-era dialects.

History

The origins, early form and development of the Hellenic language family are not well understood because of a lack of contemporaneous evidence. Several theories exist about what Hellenic dialect groups may have existed between the divergence of early Greek-like speech from the common Proto-Indo-European language and the Classical period. They have the same general outline but differ in some of the detail. The only attested dialect from this period[a] is Mycenaean Greek, but its relationship to the historical dialects and the historical circumstances of the times imply that the overall groups already existed in some form.

Scholars assume that major Ancient Greek period dialect groups developed not later than 1120 BC, at the time of the Dorian invasions—and that their first appearances as precise alphabetic writing began in the 8th century BC. The invasion would not be "Dorian" unless the invaders had some cultural relationship to the historical Dorians. The invasion is known to have displaced population to the later Attic-Ionic regions, who regarded themselves as descendants of the population displaced by or contending with the Dorians.

The Greeks of this period believed there were three major divisions of all Greek people – Dorians, Aeolians, and Ionians (including Athenians), each with their own defining and distinctive dialects. Allowing for their oversight of Arcadian, an obscure mountain dialect, and Cypriot, far from the center of Greek scholarship, this division of people and language is quite similar to the results of modern archaeological-linguistic investigation.

One standard formulation for the dialects is:[4]

Western group:

|

Central group: |

Eastern group:

|

Western group:

|

Eastern group:

|

- West Group

- Northwest Greek

- Doric

- Aeolic Group

- Aegean/Asiatic Aeolic

- Thessalian

- Boeotian

- Ionic-Attic Group

- Arcadocypriot Greek

- Arcadian

- Cypriot

West vs. non-West Greek is the strongest-marked and earliest division, with non-West in subsets of Ionic-Attic (or Attic-Ionic) and Aeolic vs. Arcadocypriot, or Aeolic and Arcado-Cypriot vs. Ionic-Attic. Often non-West is called 'East Greek'.

Arcadocypriot apparently descended more closely from the Mycenaean Greek of the Bronze Age.

Boeotian Greek had come under a strong Northwest Greek influence, and can in some respects be considered a transitional dialect, as exemplified in the poems of the Boeotian poet Pindar who wrote in Doric with a small Aeolic admixture.[6] Thessalian likewise had come under Northwest Greek influence, though to a lesser degree.

Pamphylian Greek, spoken in a small area on the southwestern coast of Anatolia and little preserved in inscriptions, may be either a fifth major dialect group, or it is Mycenaean Greek overlaid by Doric, with a non-Greek native influence.[7]

Regarding the speech of the ancient Macedonians diverse theories have been put forward, but the epigraphic activity and the archaeological discoveries in the Greek region of Macedonia during the last decades has brought to light documents, among which the first texts written in Macedonian, such as the Pella curse tablet, as Hatzopoulos and other scholars note.[8][9] Based on the conclusions drawn by several studies and findings such as Pella curse tablet, Emilio Crespo and other scholars suggest that ancient Macedonian was a Northwest Doric dialect,[10][11][9] which shares isoglosses with its neighboring Thessalian dialects spoken in northeastern Thessaly.[10][9] Some have also suggested an Aeolic Greek classification.[12][13]

The Lesbian dialect was Aeolic. For example, fragments of the works of the poet Sappho from the island of Lesbos are in Aeolian.[14]

Most of the dialect sub-groups listed above had further subdivisions, generally equivalent to a city-state and its surrounding territory, or to an island. Doric notably had several intermediate divisions as well, into Island Doric (including Cretan Doric), Southern Peloponnesus Doric (including Laconian, the dialect of Sparta), and Northern Peloponnesus Doric (including Corinthian).

All the groups were represented by colonies beyond Greece proper as well, and these colonies generally developed local characteristics, often under the influence of settlers or neighbors speaking different Greek dialects.

After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the late 4th century BC, a new international dialect known as Koine or Common Greek developed, largely based on Attic Greek, but with influence from other dialects. This dialect slowly replaced most of the older dialects, although the Doric dialect has survived in the Tsakonian language, which is spoken in the region of modern Sparta. Doric has also passed down its aorist terminations into most verbs of Demotic Greek. By about the 6th century AD, the Koine had slowly metamorphosed into Medieval Greek.

Related languages

Phrygian is an extinct Indo-European language of West and Central Anatolia, which is considered by some linguists to have been closely related to Greek.[15][16][17] Among Indo-European branches with living descendants, Greek is often argued to have the closest genetic ties with Armenian[18] (see also Graeco-Armenian) and Indo-Iranian languages (see Graeco-Aryan).[19][20]

Phonology

Differences from Proto-Indo-European

Ancient Greek differs from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) and other Indo-European languages in certain ways. In phonotactics, ancient Greek words could end only in a vowel or /n s r/; final stops were lost, as in γ?λα "milk", compared with γ?λακτο? "of milk" (genitive). Ancient Greek of the classical period also differed in both the inventory and distribution of original PIE phonemes due to numerous sound changes,[21] notably the following:

- PIE *s became /h/ at the beginning of a word (debuccalization): Latin sex, English six, ancient Greek ?ξ /héks/.

- PIE *s was elided between vowels after an intermediate step of debuccalization: Sanskrit janasas, Latin generis (where s > r by rhotacism), Greek *genesos > *genehos > ancient Greek γ?νεο? (/ɡéneos/), Attic γ?νου? (/ɡéno?s/) "of a kind".

- PIE *y /j/ became /h/ (debuccalization) or /(d)z/ (fortition): Sanskrit yas, ancient Greek ?? /hós/ "who" (relative pronoun); Latin iugum, English yoke, ancient Greek ζυγ?? /zyɡós/.

- PIE *w, which occurred in Mycenaean and some non-Attic dialects, was lost: early Doric ??ργον /wérɡon/, English work, Attic Greek ?ργον /érɡon/.

- PIE and Mycenaean labiovelars changed to plain stops (labials, dentals, and velars) in the later Greek dialects: for instance, PIE *k? became /p/ or /t/ in Attic: Attic Greek πο? /p??/ "where?", Latin quō; Attic Greek τ?? /tís/, Latin quis "who?".

- PIE "voiced aspirated" stops b? d? ?? g? g?? were devoiced and became the aspirated stops φ θ χ /p? t? k?/ in ancient Greek.

Phonemic inventory

The pronunciation of Ancient Greek was very different from that of Modern Greek. Ancient Greek had long and short vowels; many diphthongs; double and single consonants; voiced, voiceless, and aspirated stops; and a pitch accent. In Modern Greek, all vowels and consonants are short. Many vowels and diphthongs once pronounced distinctly are pronounced as /i/ (iotacism). Some of the stops and glides in diphthongs have become fricatives, and the pitch accent has changed to a stress accent. Many of the changes took place in the Koine Greek period. The writing system of Modern Greek, however, does not reflect all pronunciation changes.

The examples below represent Attic Greek in the 5th century BC. Ancient pronunciation cannot be reconstructed with certainty, but Greek from the period is well documented, and there is little disagreement among linguists as to the general nature of the sounds that the letters represent.

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | μ m |

ν n |

γ (?)1 |

||

| Plosive | voiced | β b |

δ d |

γ ɡ |

|

| voiceless | π p |

τ t |

κ k |

||

| aspirated | φ p? |

θ t? |

χ k? |

||

| Fricative | σ s2 |

h3 | |||

| Approximant | λ l |

||||

| Trill | ρ r4 |

||||

- 1 [?] occurred as an allophone of /n/ that was used before velars and as an allophone of /ɡ/ before nasals.

- 2 /s/ was assimilated to [z] before voiced consonants.

- 3 /h/ was earlier written Η, but when the same letter (eta) was co-opted to stand for a vowel, /h/ was dropped from writing, to be restored later in the form of a diacritic, the rough breathing.

- 4 /r/ was probably a voiceless /r?/ when word-initially and geminated (written ? and ??).

Vowels

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||

| Close | ι i i? |

υ y y? |

|

| Close-mid | ε ει e e? |

ο ου o o? | |

| Open-mid | η ?? |

ω ?? | |

| Open | α a a? | ||

/o?/ raised to [u?], probably by the 4th century BC.

Morphology

Greek, like all of the older Indo-European languages, is highly inflected. It is highly archaic in its preservation of Proto-Indo-European forms. In ancient Greek, nouns (including proper nouns) have five cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, and vocative), three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), and three numbers (singular, dual, and plural). Verbs have four moods (indicative, imperative, subjunctive, and optative) and three voices (active, middle, and passive), as well as three persons (first, second, and third) and various other forms.

Verbs are conjugated through seven combinations of tenses and aspect (generally simply called "tenses"): the present, future, and imperfect are imperfective in aspect; the aorist, present perfect, pluperfect and future perfect are perfective in aspect. Most tenses display all four moods and three voices, although there is no future subjunctive or imperative. Also, there is no imperfect subjunctive, optative or imperative. The infinitives and participles correspond to the finite combinations of tense, aspect, and voice.

Augment

The indicative of past tenses adds (conceptually, at least) a prefix /e-/, called the augment. This was probably originally a separate word, meaning something like "then", added because tenses in PIE had primarily aspectual meaning. The augment is added to the indicative of the aorist, imperfect, and pluperfect, but not to any of the other forms of the aorist (no other forms of the imperfect and pluperfect exist).

The two kinds of augment in Greek are syllabic and quantitative. The syllabic augment is added to stems beginning with consonants, and simply prefixes e (stems beginning with r, however, add er). The quantitative augment is added to stems beginning with vowels, and involves lengthening the vowel:

- a, ā, e, ē → ē

- i, ī → ī

- o, ō → ō

- u, ū → ū

- ai → ēi

- ei → ēi or ei

- oi → ōi

- au → ēu or au

- eu → ēu or eu

- ou → ou

Some verbs augment irregularly; the most common variation is e → ei. The irregularity can be explained diachronically by the loss of s between vowels, or that of the letter w, which affected the augment when it was word-initial. In verbs with a preposition as a prefix, the augment is placed not at the start of the word, but between the preposition and the original verb. For example, προσ(-)β?λλω (I attack) goes to προσ?βαλoν in the aorist. However compound verbs consisting of a prefix that is not a preposition retain the augment at the start of the word: α?το(-)μολ? goes to η?τομ?λησα in the aorist.

Following Homer's practice, the augment is sometimes not made in poetry, especially epic poetry.

The augment sometimes substitutes for reduplication; see below.

Reduplication

Almost all forms of the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect reduplicate the initial syllable of the verb stem. (A few irregular forms of perfect do not reduplicate, whereas a handful of irregular aorists reduplicate.) The three types of reduplication are:

- Syllabic reduplication: Most verbs beginning with a single consonant, or a cluster of a stop with a sonorant, add a syllable consisting of the initial consonant followed by e. An aspirated consonant, however, reduplicates in its unaspirated equivalent (see Grassmann's law).

- Augment: Verbs beginning with a vowel, as well as those beginning with a cluster other than those indicated previously (and occasionally for a few other verbs) reduplicate in the same fashion as the augment. This remains in all forms of the perfect, not just the indicative.

- Attic reduplication: Some verbs beginning with an a, e or o, followed by a sonorant (or occasionally d or g), reduplicate by adding a syllable consisting of the initial vowel and following consonant, and lengthening the following vowel. Hence er → erēr, an → anēn, ol → olōl, ed → edēd. This is not specific to Attic Greek, despite its name, but it was generalized in Attic. This originally involved reduplicating a cluster consisting of a laryngeal and sonorant, hence h?l → h?leh?l → olōl with normal Greek development of laryngeals. (Forms with a stop were analogous.)

Irregular duplication can be understood diachronically. For example, lambanō (root lab) has the perfect stem eilēpha (not *lelēpha) because it was originally slambanō, with perfect seslēpha, becoming eilēpha through compensatory lengthening.

Reduplication is also visible in the present tense stems of certain verbs. These stems add a syllable consisting of the root's initial consonant followed by i. A nasal stop appears after the reduplication in some verbs.[22]

Writing system

| Greek alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diacritics and other symbols | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

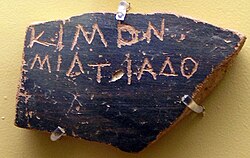

The earliest extant examples of ancient Greek writing (c.?1450 BC) are in the syllabic script Linear B. Beginning in the 8th century BC, however, the Greek alphabet became standard, albeit with some variation among dialects. Early texts are written in boustrophedon style, but left-to-right became standard during the classic period. Modern editions of ancient Greek texts are usually written with accents and breathing marks, interword spacing, modern punctuation, and sometimes mixed case, but these were all introduced later.

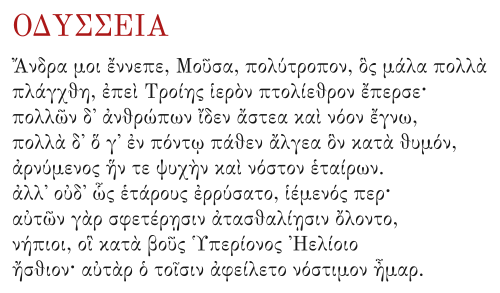

Sample texts

The beginning of Homer's Iliad exemplifies the Archaic period of ancient Greek (see Homeric Greek for more details):

Μ?νιν ?ειδε, θε?, Πηλη??δεω ?χιλ?ο?

ο?λομ?νην, ? μυρ?' ?χαιο?? ?λγε' ?θηκε,

πολλ?? δ' ?φθ?μου? ψυχ?? ??δι προ?αψεν

?ρ?ων, α?το?? δ? ?λ?ρια τε?χε κ?νεσσιν

ο?ωνο?σ? τε π?σι· Δι?? δ' ?τελε?ετο βουλ?·

?ξ ο? δ? τ? πρ?τα διαστ?την ?ρ?σαντε

?τρε?δη? τε ?ναξ ?νδρ?ν κα? δ?ο? ?χιλλε??.

The beginning of Apology by Plato exemplifies Attic Greek from the Classical period of ancient Greek. (The second line is the IPA, the third is transliterated into the Latin alphabet using a modern version of the Erasmian scheme.)

?τι

[hóti

Hóti

μ?ν

men

mèn

?με??,

hy?mê?s

hūme?s,

|

?

???

?

?νδρε?

ándres

ándres

?θηνα?οι,

at???na??i?oi

Athēna?oi,

|

πεπ?νθατε

pepónt?ate

pepónthate

|

?π?

hypo

hupò

τ?ν

t???n

t?n

?μ?ν

em????

em?n

κατηγ?ρων,

kat??ɡór??n

katēgórōn,

|

ο?κ

o?k

ouk

ο?δα·

o??da

o?da:

‖

?γ?

eɡ???

eg?

δ' ο?ν

d???

d' o?n

κα?

kai?

kaì

α?τ??

au?tos

autòs

|

?π'

hyp

hup'

α?τ?ν

au?t???n

autōn

?λ?γου

olíɡo?

olígou

?μαυτο?

emau?t??

emauto?

|

?πελαθ?μην,

epelat?óm??n

epelathómēn,

|

ο?τω

hǔ?t??

hoútō

πιθαν??

pit?an???s

pithan?s

?λεγον.

éleɡon

élegon.

‖

Κα?τοι

kaí?toi?

Kaítoi

?ληθ??

al??t?éz

alēthés

γε

ɡe

ge

|

??

h??s

hōs

?πο?

épos

épos

ε?πε?ν

e?pê?n

eipe?n

|

ο?δ?ν

o?den

oudèn

ε?ρ?κασιν.

e?r???ka?sin

eir?kāsin.

‖]

How you, men of Athens, are feeling under the power of my accusers, I do not know: actually, even I myself almost forgot who I was because of them, they spoke so persuasively. And yet, loosely speaking, nothing they have said is true.

Modern use

In education

The study of Ancient Greek in European countries in addition to Latin occupied an important place in the syllabus from the Renaissance until the beginning of the 20th century. This was true as well in the United States, where many of the nation's Founders received a classically based education.[23] Latin was emphasized in American colleges, but Greek also was required in the Colonial and Early National eras,[24] and the study of ancient Greece became increasingly popular in the mid-to-late Nineteenth Century, the age of American philhellenism.[25] In particular, female intellectuals of the era designated the mastering of ancient Greek as essential in becoming a "woman of letters."[26]

Ancient Greek is still taught as a compulsory or optional subject especially at traditional or elite schools throughout Europe, such as public schools and grammar schools in the United Kingdom. It is compulsory in the liceo classico in Italy, in the gymnasium in the Netherlands, in some classes in Austria, in klasi?na gimnazija (grammar school – orientation: classical languages) in Croatia, in classical studies in ASO in Belgium and it is optional in the humanities-oriented gymnasium in Germany, usually as a third language after Latin and English, from the age of 14 to 18. In 2006/07, 15,000 pupils studied ancient Greek in Germany according to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, and 280,000 pupils studied it in Italy.[27]

It is a compulsory subject alongside Latin in the humanities branch of the Spanish Baccalaureate. Ancient Greek is taught at most major universities worldwide, often combined with Latin as part of the study of classics. In 2010 it was offered in three primary schools in the UK, to boost children's language skills,[28][29] and was one of seven foreign languages which primary schools could teach 2014 as part of a major drive to boost education standards.[30][needs update]

Ancient Greek is taught as a compulsory subject in all gymnasiums and lyceums in Greece.[31][32] Starting in 2001, an annual international competition "Exploring the Ancient Greek Language and Culture" (Greek: Διαγωνισμ?? στην Αρχα?α Ελληνικ? Γλ?σσα και Γραμματε?α) was run for upper secondary students through the Greek Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, with Greek language and cultural organisations as co-organisers.[33] It appears to have ceased in 2010, having failed to gain the recognition and acceptance of teachers.[34]

Modern real-world usage

Modern authors rarely write in ancient Greek, though Jan K?esadlo wrote some poetry and prose in the language, and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone,[35] some volumes of Asterix,[36] and The Adventures of Alix have been translated into ancient Greek. ?ν?ματα Kεχιασμ?να (Onomata Kechiasmena) is the first magazine of crosswords and puzzles in ancient Greek.[37] Its first issue appeared in April 2015 as an annex to Hebdomada Aenigmatum. Alfred Rahlfs included a preface, a short history of the Septuagint text, and other front matter translated into ancient Greek in his 1935 edition of the Septuagint; Robert Hanhart also included the introductory remarks to the 2006 revised Rahlfs–Hanhart edition in the language as well.[38] Akropolis World News reports weekly a summary of the most important news in ancient Greek.[39]

Ancient Greek is also used by organizations and individuals, mainly Greek, who wish to denote their respect, admiration or preference for the use of this language. This use is sometimes considered graphical, nationalistic or humorous. In any case, the fact that modern Greeks can still wholly or partly understand texts written in non-archaic forms of ancient Greek shows the affinity of the modern Greek language to its ancestral predecessor.[39]

Ancient Greek is often used in the coinage of modern technical terms in the European languages: see English words of Greek origin. Latinized forms of ancient Greek roots are used in many of the scientific names of species and in scientific terminology.

See also

- Ancient Greek dialects – Varieties of Ancient Greek in classical antiquity

- Ancient Greek grammar – Grammar of the Ancient Greek language

- Ancient Greek accent

- Greek alphabet – Script used to write the Greek language

- Greek diacritics – Marks added to letters in Greek

- Greek language – Indo-European language

- Hellenic languages – Branch of Indo-European language family

- Katharevousa – Former prestige form of the Modern Greek language

- Koine Greek – Dialect of Greek in the ancient world

- List of Greek and Latin roots in English

- List of Greek phrases (mostly ancient Greek)

- Medieval Greek – Medieval stage of the Greek language

- Modern Greek – Dialects and varieties of the Greek language spoken in the modern era

- Mycenaean Greek – Earliest attested form of the Greek language, from the 16th to the 12th century BC

- Proto-Greek language – Last common ancestor of all varieties of Greek

- Varieties of Modern Greek – Dialects and differences between the written standard and spoken speech

Notes

- ^ Mycenaean Greek is imprecisely attested and somewhat reconstructive due to its being written in an ill-fitting syllabary (Linear B).

References

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (28 October 2015). Dictionary of Languages: The definitive reference to more than 400 languages. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4081-0214-5. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Ralli, Angela (2012). "Greek". Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire. 90 (3): 964. doi:10.3406/rbph.2012.8269. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Hose, Martin; Schenker, David (2015). A Companion to Greek Literature. John Wiley & Sons. p. 445. ISBN 978-1118885956.

- ^ Newton, Brian E.; Ruijgh, Cornelis Judd (13 April 2018). "Greek Language". Encyclop?dia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Roger D. Woodard (2008), "Greek dialects", in: The Ancient Languages of Europe, ed. R. D. Woodard, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 51.

- ^ Gerber, Douglas E. (1997). A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets. Brill. p. 255. ISBN 90-04-09944-1.

- ^ Skelton, Christina (2017). "Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia" (PDF). Classical Antiquity. 36 (1): 104–129. doi:10.1525/ca.2017.36.1.104. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon (2002). "Macedon, Thessaly and Boiotia". The Greek World, 479–323 BC (Third ed.). Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 0-415-16326-9.

- ^ a b c Hatzopoulos, Miltiades B. (2018). "Recent Research in the Ancient Macedonian Dialect: Consolidation and New Perspectives". In Giannakis, Georgios K.; Crespo, Emilio; Filos, Panagiotis (eds.). Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects: From Central Greece to the Black Sea. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 299–324. ISBN 978-3-11-053081-0. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Crespo, Emilio (2018). "The Softening of Obstruent Consonants in the Macedonian Dialect". In Giannakis, Georgios K.; Crespo, Emilio; Filos, Panagiotis (eds.). Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects: From Central Greece to the Black Sea. Walter de Gruyter. p. 329. ISBN 978-3-11-053081-0.

- ^ Dosuna, J. Méndez (2012). "Ancient Macedonian as a Greek dialect: A critical survey on recent work (Greek, English, French, German text)". In Giannakis, Georgios K. (ed.). Ancient Macedonia: Language, History, Culture. Centre for Greek Language. p. 145. ISBN 978-960-7779-52-6.

- ^ Hammond, N.G.L (1997). Collected Studies: Further studies on various topics. A.M. Hakkert. p. 79. Archived from the original on 28 September 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Worthington, Ian (2012). Alexander the Great: A Reader. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-136-64003-2. Archived from the original on 28 September 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Reynolds, Margaret (2001). The Sappho Companion. London: Vintage. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-09-973861-9.

- ^ Brixhe, Cl. "Le Phrygien". In Fr. Bader (ed.), Langues indo-européennes, pp. 165–178, Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Brixhe, Claude (2008). "Phrygian". In Woodard, Roger D (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–80. ISBN 978-0-521-68496-5. "Unquestionably, however, Phrygian is most closely linked with Greek." (p. 72).

- ^ Obrador-Cursach, Bartomeu (1 December 2019). "On the place of Phrygian among the Indo-European languages". Journal of Language Relationship (in Russian). 17 (3–4): 243. doi:10.31826/jlr-2019-173-407. S2CID 215769896.

With the current state of our knowledge, we can affirm that Phrygian is closely related to Greek.

- ^ James Clackson. Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture. Blackwell, 2004, p. 181.

- ^ Henry M. Hoenigswald, "Greek", The Indo-European Languages, ed. Anna Giacalone Ramat and Paolo Ramat (Routledge, 1998 pp. 228–260), p. 228.

BBC: Languages across Europe: Greek Archived 14 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European language and culture: an introduction. Malden, Mass: Blackwell. pp. 226–231. ISBN 978-1405103152. OCLC 54529041.

- ^ Palmer, Leonard (1996). The Greek Language. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-8061-2844-3.

- ^ Thirty-six of the eighty-nine men who signed the Declaration of Independence and attended the Constitutional Convention went to a colonial college, all of which offered only the classical curricula. Richard M. Gummere, The American Colonial Mind and the Classical Tradition, p.66 (1963). Admission to Harvard, for example, required that the applicant: "Can readily make and speak or write true Latin prose and has skill in making verse, and is competently grounded in the Greek language so as to be able to construe and grammatically to resolve ordinary Greek, as in the Greek Testament, Isocrates, and the minor poets." Meyer Reinhold, Classica Americana: The Greek and Roman Heritage in the United States, p.27 (1984).

- ^ Harvard's curriculum was patterned after those of Oxford and Cambridge, and the curricula of other Colonial colleges followed Harvard's. Lawrence A. Cremin, American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607–1783, pp. 128–129 (1970), and Frederick Rudolph, Curriculum: A History of the American Undergraduate Course of Study Since 1636, pp. 31–32 (1978)

- ^ Caroline Winterer, The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Cultural Life, 1780–1910, pp.3–4 (2002).

- ^ Yopie Prins, Ladies' Greek: Victorian Translations of Tragedy, pp. 5–6 (2017). See also Timothy Kearley, Roman Law, Classical Education, and Limits on Classical Participation in America into the Twentieth-Century, pp. 54–55, 97–98 (2022)

- ^ "Ministry publication" (PDF). www.edscuola.it. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "Ancient Greek 'to be taught in state schools'". The Daily Telegraph. 30 July 2010. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Now look, Latin's fine, but Greek might be even Beta" Archived 3 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, TES Editorial, 2010 – TSL Education Ltd.

- ^ More primary schools to offer Latin and ancient Greek Archived 13 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph, 26 November 2012

- ^ "Ωρολ?γιο Πρ?γραμμα των μαθημ?των των Α, Β, Γ τ?ξεων του Hμερησ?ου Γυμνασ?ου". Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "ΩΡΟΛΟΓΙΟ ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΓΕΝΙΚΟΥ ΛΥΚΕΙΟΥ". Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Annex to 2012 Greek statistics" (PDF). UNESCO. 2012. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Proceedings of the 2nd Pan-hellenic Congress for the Promotion of Innovation in Education. Vol. II. 2016. p. 548.

- ^ Areios Potēr kai ē tu philosophu lithos, Bloomsbury 2004, ISBN 1-58234-826-X

- ^ "Asterix speaks Attic (classical Greek) – Greece (ancient)". Asterix around the World – the many Languages of Asterix. 22 May 2011. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "Enigmistica: nasce prima rivista in greco antico 2015". 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Rahlfs, Alfred, and Hanhart, Robert (eds.), Septuaginta, editio altera (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2006).

- ^ a b "Akropolis World News". www.akwn.net. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016.

Further reading

- Adams, Matthew. "The Introduction of Greek into English Schools." Greece and Rome 61.1: 102–13, 2014. JSTOR 43297490.

- Allan, Rutger J. "Changing the Topic: Topic Position in Ancient Greek Word Order." Mnemosyne: Bibliotheca Classica Batava 67.2: 181–213, 2014.

- Athenaze: An Introduction to Ancient Greek (Oxford University Press). [A series of textbooks on Ancient Greek published for school use.]

- Bakker, Egbert J., ed. A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2010.

- Chantraine, Pierre. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, new and updated edn., edited by Jean Taillardat, Olivier Masson, & Jean-Louis Perpillou. 3 vols. Paris: Klincksieck, 2009 (1st edn. 1968–1980).

- Christidis, Anastasios-Phoibos, ed. A History of Ancient Greek: from the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Easterling, P. and Handley, C. Greek Scripts: An Illustrated Introduction. London: Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, 2001. ISBN 0-902984-17-9

- Fortson, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. 2d ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Hansen, Hardy and Quinn, Gerald M. (1992) Greek: An Intensive Course, Fordham University Press

- Horrocks, Geoffrey. Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers. 2d ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Janko, Richard. "The Origins and Evolution of the Epic Diction." In The Iliad: A Commentary. Vol. 4, Books 13–16. Edited by Richard Janko, 8–19. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992.

- Jeffery, Lilian Hamilton. The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece: Revised Edition with a Supplement by A. W. Johnston. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990.

- Morpurgo Davies, Anna, and Yves Duhoux, eds. A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Vol. 1. Louvain, Belgium: Peeters, 2008.

- Philip S. Peek (2021). Ancient Greek I: A 21st Century Approach. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/obp.0264. ISBN 978-1-80064-655-1.

- Philip S. Peek (2025). Αncient Greek II: A 21st Century Approach. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/obp.0441. ISBN 978-1-80511-476-5.

External links

- Classical Greek Online by Winfred P. Lehmann and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Online Greek resources – Dictionaries, grammar, virtual libraries, fonts, etc.

- Alpheios – Combines LSJ, Autenrieth, Smyth's grammar and inflection tables in a browser add-on for use on any web site

- Ancient Greek basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Ancient Greek Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh list appendix)

- . Encyclop?dia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Slavonic – online editor for Ancient Greek

- glottothèque – Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of videos on various Ancient Indo-European languages, including Ancient Greek

- Community courses on Memrise

Grammar learning

- A more extensive grammar of the Ancient Greek language written by J. Rietveld Archived 7 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Recitation of classics books

- Perseus Greek dictionaries

- Greek-Language.com – Information on the history of the Greek language, application of modern Linguistics to the study of Greek, and tools for learning Greek

- Free Lessons in Ancient Greek, Bilingual Libraries, Forum

- A critical survey of websites devoted to Ancient Greek

- Ancient Greek Tutorials – Berkeley Language Center of the University of California

- A Digital Tutorial For Ancient Greek Based on White's First Greek Book

- New Testament Greek

- Acropolis World News – A summary of the latest world news in Ancient Greek, Juan Coderch, University of St Andrews